From the Archives: Dovecrest Restaurant & Thanksgiving

Belonging(s): “A close relationship among a group and personal or public effects”

“Asco wequassinummis, neetompooag” (Hello my friends)!

Hello and Wunne Taubutantamoonk! Welcome to the Belongings Blog’s next installment of the From the Archives series, in which our Archivist Anthony Belz shares some of the more interesting materials found in the Tomaquag Museum archival collections. This fifth installment is lengthy and focuses on the Dovecrest Restaurant which was located in Exeter, Rhode Island adjacent to where the Tomaquag Museum is today. The Dovecrest Restaurant was an award winning and well renowned Indigenous cultural and culinary fixture in southern Rhode Island from 1963 until its closure in 1984.

In the mid-1950s, Eleanor (1918-2019) and Ferris Babcock Dove (1915-1983), members of the Narragansett/Niantic Indian Tribe, decided to move their family to a large house and property located on Summit Road in the heart of Arcadia Village in Exeter, Rhode Island. Ferris Dove (Chief Roaring Bull) who grew up in Charlestown was a graduate of Bacone Indian College in Oklahoma and had a stint in the Civilian Conservation Corps during the Great Depression. After the Depression, Ferris returned home and had been farming potatoes before eventually landing a job as a supervisor at the General Dynamics boat plant in Groton, Connecticut. Ferris was also later the Town Moderator for the Town of Exeter, also served as Tax Accessor, and was notably the Postmaster for the Rockville Post Office (the only Indigenous person in the country at that time to serve as a Postmaster and still only one of a handful in history) just down the road from Dovecrest. Eleanor (Pretty Flower) grew up in East Providence where she graduated high school and worked as a waitress in Providence. Later, while raising four children served on the Board of Canvassers for Exeter and President of the Parent Teacher Association as well as a member of the Hospital Aid Association in Westerly. Both were members of The Sons and Daughters of the First Americans, local Indigenous organization founded by Redwing.

The Doves named the property Dovecrest because of its location on the crest of a hill near a aptly named stream called Roaring Brook, a tributary of the Wood River. This stream runs off of a large lake called Browning Mill Pond which is responsible for the number of mills that were in operation in Arcadia Village in the 19th and early 20th centuries (Now part of the Arcadia Management Area, a Rhode Island State Park). The house itself was constructed sometime between 1850 and 1875 and had originally served as the home of the mill owner James Harris, who in 1836 established the Arcadia Cotton Mill. The west end of the building, a later addition to the original house was constructed between 1900 and 1925 and for many years the location of a small Episcopal church, of which a bell tower remains today, serving as a reminder of its former use.

Not too long after the Doves moved to Dovecrest they decided to open up a restaurant on the property, so they remodeled a small house adjacent to their home and called it fittingly, the Dovecrest Restaurant. Eleanor came from a family of chefs. Her father Joseph Spears, Jr. and grandfather Joseph Spears were both chefs. Both Ferris and Eleanor had both worked in catering businesses at the Watch Hill Inn and in Charlestown before they decided to open a restaurant. The Doves understood the catering business and agreed that owning and operating a restaurant was hard work, but an honest profession and by being self employed next to their own home provided security and economic stability for their family of four children, Mark, Paulla, Dawn and Lori. Around the same time, they converted the former church space they had been renting out for events (such as wedding receptions, anniversary and other types of parties, buffets and dinner dances-which they would cater) and named it the Dovecrest Trading Post, which sold a variety of Indigenous art, clothing and jewelry from all over the United States.

Ferris and Eleanor Dove created a spacious and beautifully landscaped property at Dovecrest in the quiet and out of the way Arcadia Village. Dovecrest quickly became a place that was a welcoming and comfortable environment for their family and patrons of the restaurant alike. This included a spacious sunny deck (later enclosed) where guests could dine al fresco overlooking a tiered garden and Roaring Brook. In addition there was an apple orchard in the rear of the property and games were made available outside in the yard like horseshoes, badminton and croquet. It was definitely the heart of the community in the small hamlet of Arcadia Village.

At the Dovecrest Restaurant, the main dining room located upstairs and was called the “Indian Room,” and could seat up to 90 people for private events and served both lunch and dinner. The Cocktail Lounge was located downstairs in the basement and was entered from a separate door and had a full service bar that served snacks and included a juke box. On occasion outside entertainment was provided by small stringed instrument groups who would encourage patrons to sing along with them. Upstairs in the Indian Room, Redwing, an internationally known Narragansett/Wampanoag cultural ambassador, and who lived upstairs in Dovecrest, was famous at the restaurant for reading tea leaves for the guests during the afternoons as they would enjoy “delicious sandwiches, dainty cakes and ‘magic’ tea.”

Initially, when the Doves had opened Dovecrest Restaurant the menu offered “standard steakhouse fare,” which was typically considered main dishes such as beef steaks, pork chops chicken and seafood with sides of vegetables and hearty soups, stews and chowders- your typical Yankee style meat and potatoes type restaurant. (This was very much the backbone of the Dovecrest Restaurant for its entire existence.) It wasn’t until a few years after Dovecrest was in operation that patrons of the restaurant noticed that the Doves were preparing different meals for their children in the room behind the kitchen. These meals comprised of wild meats, or “game” meats. Soon, customers were asking that if instead of ordering the standard steakhouse fare, they were able to order dishes such as venison stew and creamed dried cod. Venison was of course an important staple for the Indigenous people throughout time on both the North and South American continents. Venison was essential to both survival and culture as the white tailed deer provided not only food, but clothing, adornments and tools. Ferris, in his own words, “When I was growing up in Charlestown, we depended on food like venison. We would have feasts of venison steaks, oysters we pulled from the bay, Johnnycakes and potatoes. This was 1930, and only the poor people were eating that stuff. Now it’s a delicacy. Isn’t it funny how things change?”

And things did change. Slowly, but surely the Doves began incorporating wild game and other traditional Indigenous recipes, some that Eleanor had learned from her father, Joseph Spears, Sr. (who had also been a chef at the University Club in Providence) into the menu. These wild games were then appeared on for special occasions or whenever wild game or shellfish happened to be available and/or in season. Eleanor said she tried to always keep one game dish on the menu, but it was often difficult to have a steady stock on hand. Many of the wild game was procured locally, from friends and neighbors who hunted, but for other types of game, such as bison they had to rely on private, out of state distributors such as ranch in Western Massachusetts or Iron Gate Products in Manhattan.

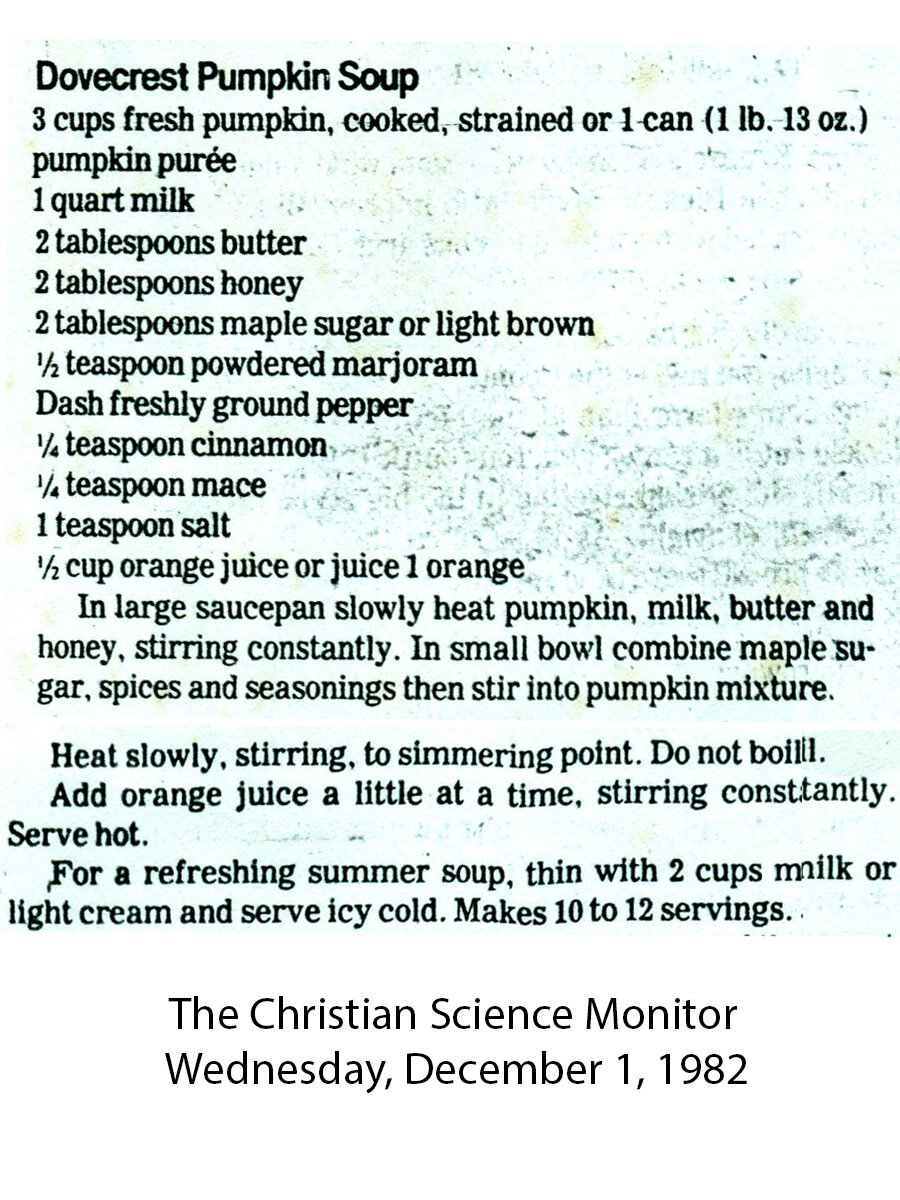

As the specialty wild game dishes began appearing on the menu, word traveled fast and Dovecrest started to become well known as a restaurant that was not only owned and operated by Indigenous people-at that time the only such establishment east of the Mississippi River-but Indigenous people who were also serving traditional Indigenous foods in this small, out of the way place in rural Exeter. One of the dishes which became a specialty at Dovecrest was a “briny fresh clam chowder” which were of course locally sourced from Narragansett Bay and other locations in Rhode Island and were shucked by Ferris every Friday and according to Eleanor “does it faster than anyone I’ve ever seen.”

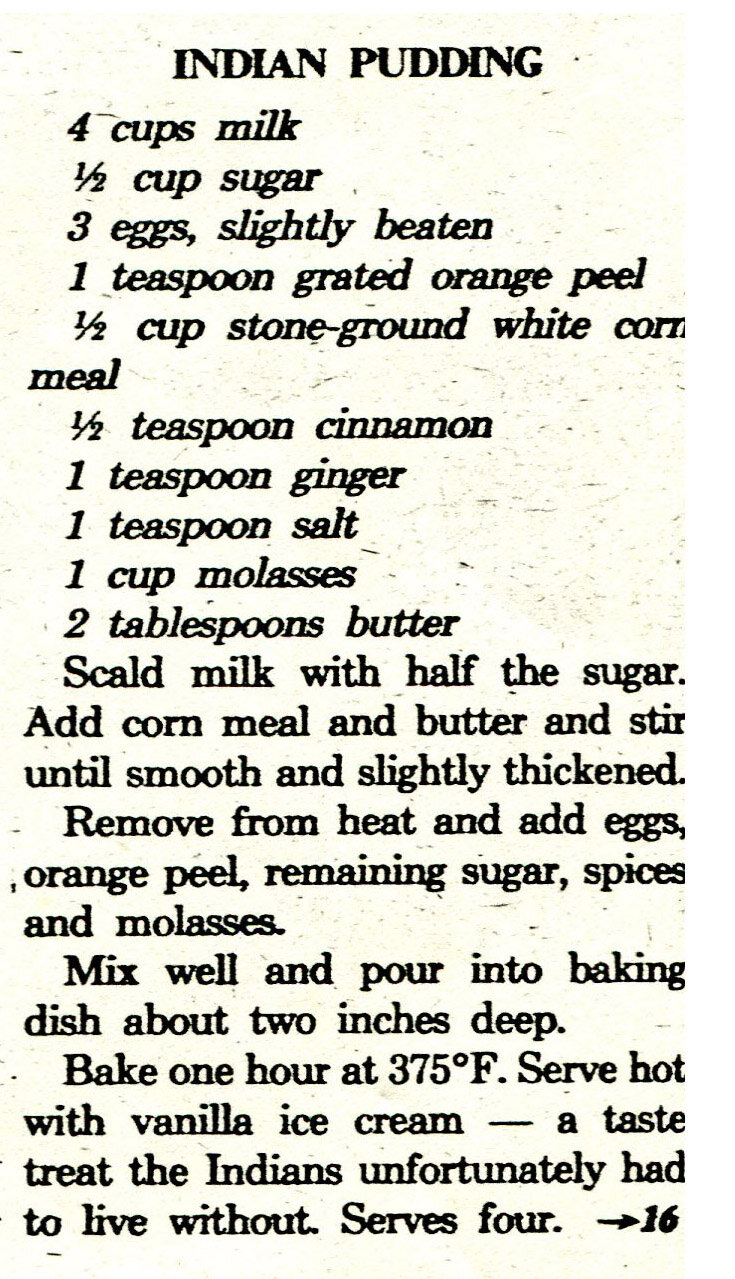

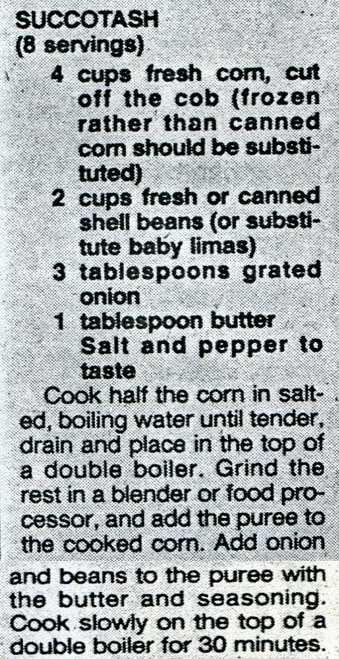

In addition to the venison stew, creamed dried cod and briny; or Rhode Island style clam chowder, Dovecrest entrees on the menu could include bison steak and pie, quahog pie, venison steak and pie, rabbit stew, squirrel pie, racoon pie, bear, elk, succotash, Indian pudding-and what they became most famous for, Johnnycakes. Johnnycakes, or “Journey cakes” as they were known during the contact (Colonial) period, were a traditional staple of Indigenous people throughout North America and the Caribbean before the invasion of Europeans and was quickly adopted by European colonists and anglicized into what we know now as Johnnycakes. Usually (but not always) they are made out of ground white flint maize, water, milk and butter, salted with a little sugar and cooked on a griddle until deep golden brown, Johnnycakes then became a staple of European colonial life and like many of the plants and animals in the Americas slowly had their Indigenous roots erased through time. Johnnycakes were served plain, as is, or with additional local, seasonal ingredients such as maple syrup, blueberries and cranberries.

Over the years as their reputation grew, Dovecrest Restaurant was recognized in many ‘Best of” guides, winning rave reviews for their Johnnycakes as often the best in the state (and even some said New England) appearing in a New York Times article ‘Cuisine as American as Raccoon Pie’ in December 9, 1981 and even winning a 1982 Ocean Spray Cranberry Salute to American Food Award in Pittsburgh in addition to a USA Today article, ‘On The Menu Succotash and Venison.’ All of the awards and accolades were hard earned and well deserved for Dovecrest Restaurant, especially the Dove matriarch Eleanor, who was the primary chef and ran the kitchen. According to Ferris, “she’s the cook and I’m the waiter.” In addition to Ferris’ clam shucking, bartending and wait duties, Dovecrest Restaurant and Trading Post was a family operation and relied on the help of close family members such as their children, Mark, Paulla, Dawn and Lori and later granddaughters Elisabeth Dove (Manning) and Lorén Wilson (Spears) as well as Eleanor’s father Joseph Spears, Jr. and Ferris’ mother Mimi Babcock Dove as well as other extended family members and local tribal members.

As the Dovecrest Restaurant name began to grow beyond Exeter, throughout Rhode Island and into New England and beyond, so too did the Tomaquag Indian Memorial Museum. Redwing (Mary E. Congdon, 1896-1987) was the co-founder and curator for the Tomaquag Museum when it opened in Ashaway in 1958, but had moved into Dovecrest in the late 1960s after the other co-founder of the museum, Eva L. Butler passed away and the property there was sold, leaving the museum without a home after almost 11 years in existence. Instead of letting the Tomaquag Museum fade into obscurity, the Doves graciously and with great foresight invited both Redwing and the Tomaquag Museum to relocate to Dovecrest together. The Tomaquag Museum, Redwing, Dovecrest Restaurant and Trading Post immediately became synonymous with one another and combined Indigenous food ways, culture and art all in one location. The restaurant, trading post and the addition of Tomaquag Indian Memorial Museum-to this day the only Indigenous operated museum in Rhode Island- created a truly unique and special place where Indigenous and non-Indigenous people alike could gather together for food, arts and crafts, and cultural events such celebrating a number of the Indigenous thirteen thanksgivings.

Redwing had become a fixture at Dovecrest Restaurant through reading tea leaves, but she was well known throughout Rhode Island, Southern New England and even internationally for her storytelling and cultural knowledge for the benefit of the Indigenous people of Rhode Island and Southern New England. She was a member of both the Narragansett/Niantic and the Wampanoag Tribes. By combining her vast cultural knowledge with the restaurant’s Indigenous food ways, The Tomaquag Museum and Dovecrest were able to bring Indigenous thanksgivings to people in a way that could not be found anywhere else, except at a powwow. Through Redwing and the Tomaquag Museum, Dovecrest hosted Maple Sugar (March), Strawberry (June), Green Bean (July), Cranberry (September), Hunter (November) and Nikkomo ‘Winter Moon’ (December) thanksgivings. Each of these thanksgivings represented not only the full moons during the year, but most are named for an accompanying food that is seasonally available in each moon cycle. The Tomaquag Museum and Redwing would host the thanksgivings, and Dovecrest Restaurant would provide the food, such as Green Bean thanksgiving, where a traditional clam bake was held.

For non-Indigenous and Indigenous people alike, the thanksgiving celebration held every third Thursday in November is an integral part of the American psyche. The myth of the First Thanksgiving between the Puritan Pilgrims of Plymouth and the Indigenous Wampanoag was the beginning of American history for the European colonists, but for many Indigenous people it marks a National Day of Mourning. The Wampanoag took pity on the Pilgrims dire situation during their first brutal New England winter, something that they were completely and woefully unprepared for. The Wampanoag used the feast as a way to show the wayward strangers that the bounties of nature were all around them and that friendship was found in sharing the land and all of its resources equitably.

For Dovecrest Restaurant, the annual November thanksgiving was an opportunity to share the bounty of the Narragansett/Niantic lands through traditional, local ingredients that included game meats such as venison, raccoon and bear; seafood such as quahogs; vegetables like as the three sisters of squash, beans and maize; fruits such as strawberries, blueberries and cranberries as well as maple syrup. November thanksgiving was always a popular day at Dovecrest Restaurant and it was not only a means to showcase Indigenous food ways to the non-Indigenous population but to also educate them about the abundance of foods that the Indigenous peoples of New England brought to the American table and that Indigenous food is American food.

Today, Indigenous food sovereignty is a very integral part of understanding and reclaiming Indigenous cultural identity, solving health and nutritional issues among Indigenous communities throughout the hemisphere, extends to land rights and acknowledgements, self governance, self reliance, community building and environmental sustainability.

Programs such as the Narragansett Food Sovereignty Initiative (NFSI), a collaborative effort by Narragansett Tribal members Cassius and Dawn Spears which began 2015, has demonstrated that food sovereignty is integral for the continued cultural and spiritual revitalization of the tribe and has been a very successful program for their community.

Time For Lunch Podcast: Giving Thanks! Featuring Lorén Spears, Executive Director of the Tomaquag Museum

Thank you very much for reading this longer than usual From The Archives. Happy Thanksgiving from all of us at the Tomaquag Museum!

In Honor of Ferris and Eleanor Dove and the Dovecrest Restaurant, I have included four recipes below so you can add your own taste of Dovecrest and true Indigenous food to your Thanksgiving table. While you give thanks for your Indigenous foods please acknowledge that you are standing on Indigenous lands.

If you have any memories of Dovecrest, please comment below! We would love to hear from you.

Anthony M. Belz, Archivist/Collections Manager

Archival images such as those featured in this blog post facilitate conversations about Indigenous traditional lifeways, art, representation/stereotypes and pervasive historical and cultural misconceptions in modern society, as well as equity and sovereignty issues. Archival materials also aid greatly in research, exhibit development, publications, films and other collaborative projects.

If you would like to support the care of archival documents, photographs, maps & more at the Tomaquag Museum please Donate Now. If you have any ideas for what you would like to see as part of this blog series, please comment below. Thank you for reading and we hope to see you at the museum in the future!

P.S. Extremely recently, as in while I was writing this blog post recently, at the beginning of November, the Rhode Island Historical Society Film Archivist & Curator of Recorded Media, Becca Bender unearthed in their Moving Image and Recorded Sound archives a one minute and twenty seconds of footage at Dovecrest Restaurant on Thanksgiving, November 28, 1974. Watch it below!

Dovecrest Thanksgiving Menu. Front Cover. Tomaquag Museum Archives.

Dovecrest Restaurant Menu. Inside Page. Tomaquag Museum Archives.

Eleanor (Pretty Flower) Dove. Tomaquag Museum Friendship Circle, Dovecrest. Late 1970s. Tomaquag Museum Archives.

Ferris Babcock Dove and Eleanor S. Dove, circa 1960s. Tomaquag Museum Archives

Dovecrest, Home of the Ferris and Eleanor Dove Family, circa 1950s. Tomaquag Museum Archives.

Dovecrest Restaurant, circa early1960s. Tomaquag Museum Archives.

Eleanor Dove and a giant cabbage, Dovecrest Restaurant, early 1960s. Tomaquag Museum Archives.

The Sons and Daughters of the First Americans Ball Invitation. Dovecrest, 1957. Tomaquag Museum Archives. Princess Red Wing Collection.

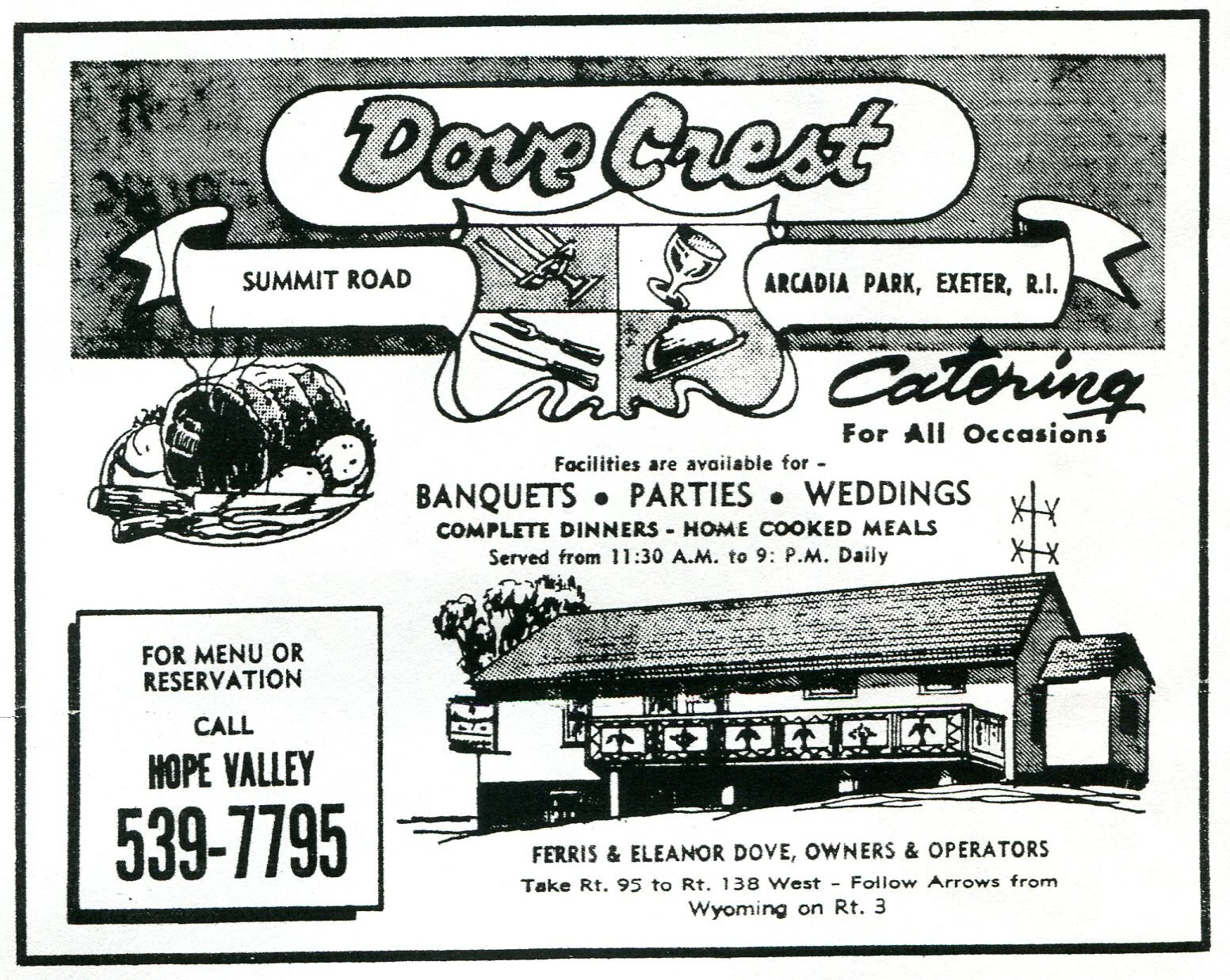

Dovecrest Yellow Pages Advertisement. 1960s. Tomaquag Museum Archives.

Dovecrest Restaurant and Cocktail Lounge. Post Card. 1970s. Tomaquag Museum Archives.

Dovecrest Restaurant “Indian Room.” Postcard. 1960s. Tomaquag Museum Archives.

Dovecrest Trading Post. Postcard. 1960s. Tomaquag Museum Archive.

Dawn Dove and Mimi Babcock Dove, Dovecrest Restaurant, late 1960s. Tomaquag Museum Archives.

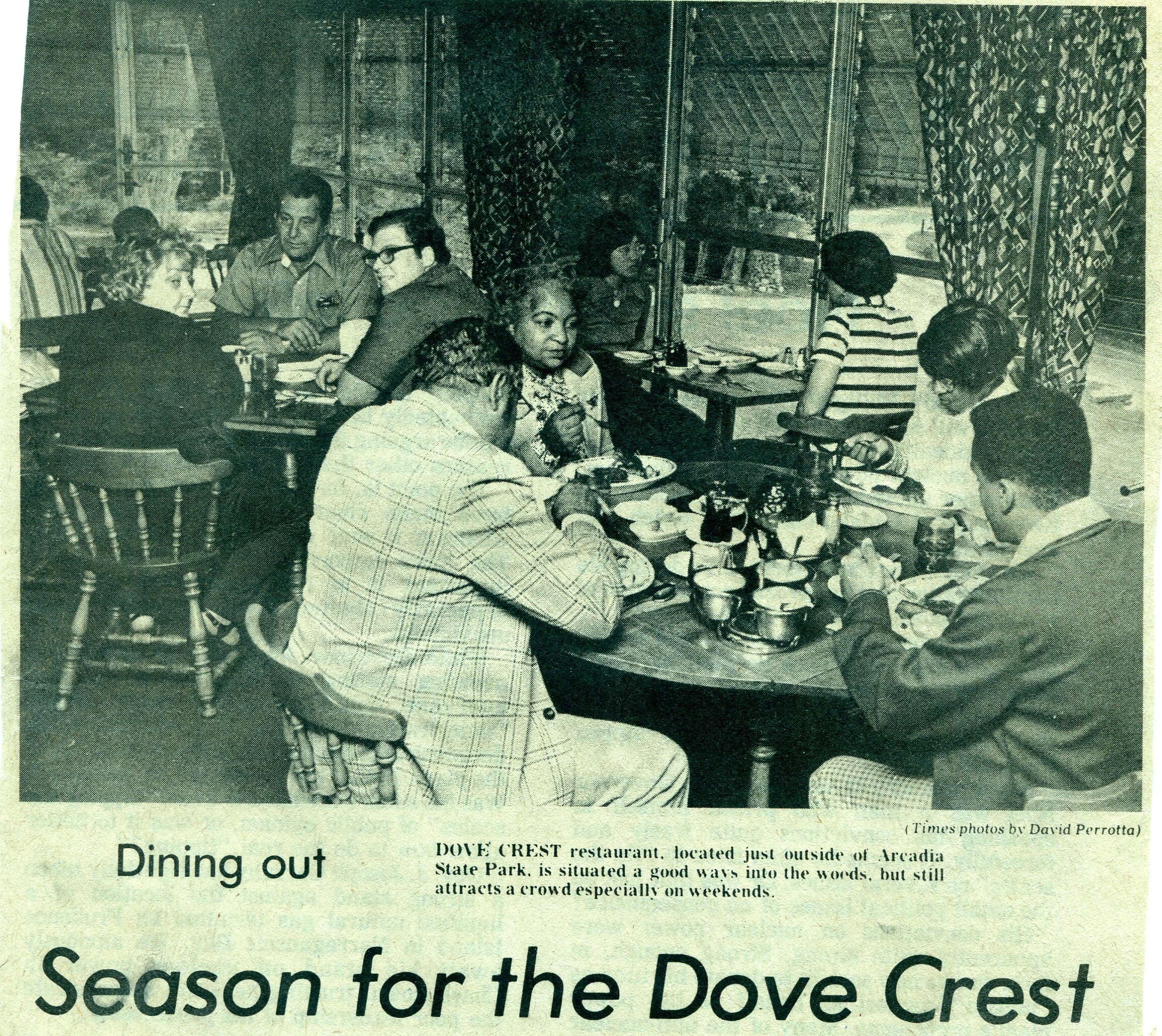

Season For Dovecrest. Chariho Times. October 5, 1977. Tomaquag Museum Archives.

Tomaquag Museum Advertisement. 1978 Tomaquag Museum Archives.

Dovecrest from Summit Road and Roaring Brook. circa 1970s. Tomaquag Museum Archives.

Eleanor Dove serves guest at Dovecrest. Late 1970s. Tomaquag Museum Archives.

Dovecrest Indian Restaurant and Trading Post Sign. 1980s. Tomaquag Museum Archives.

Dovecrest Restaurant Cocktail Lounge Teepee Entrance. Late 1970s. Tomaquag Museum Archives.

Ocean Spray Cranberry Salute to American Food Award Winners, 1982. Photocopy in Tomaquag Museum Archives.

1982 Ocean Spray Cranberry Salute to American Food Award. Ferris and Eleanor Dove, Recipients. Tomaquag Museum Collections.