Stolen Lands and Stolen People…On the Path of Resilience

Belonging(s): “A close relationship among a group and personal or public effects”

“Asco wequassinummis, neetompooag” (Hello my friends)!

Welcome back to the Belongings Blog. I am Chrystal Mars Baker, Narragansett Nation Citizen and Education Coordinator for Tomaquag Museum and this is my very first ever blog post! In my short time here, I have had the privilege of being scheduled to staff the Away From Home/Stolen Relations Exhibit hosted by Tomaquag Museum on the University of Rhode Island campus from November 10, 2021 until January 7, 2022. A thank you to those who visited the exhibit by showing your interest in the history of Indigenous peoples by engaging with this very powerful and conversation invoking exhibit. The exhibit had over 1000 visitors and the opportunity to share its content from an Indigenous perspective has been both an emotionally moving and rewarding experience as it is important for we, as Indigenous people, to have our voices heard and our stories known.

One question that was asked by so many of you was regarding the “trees depicted in the background design on so many of the panels.’ We have heard from the designer and he said “my design theory for the tree rings and blocks were a vague nod at trees chopped down for European progress as it applies to the indigenous youth (the trees) and their attempted assimilation/removal from their heritage.

The other most frequently asked question was whether there were any Narragansett children “stolen” from their homes and taken to boarding schools? The short answer is yes--but not in the same manner as those stories shared in the exhibit. I would like to share with you a bit of my people’s history to answer this question more accurately.

When European colonizers found their way to these shores in the early 17th century, they began their efforts to systematically destroy the social and political life of the Indigenous people of this hemisphere. In 1675, two centuries before the United States established the first federal boarding school, the Narragansett Nation suffered a devastating blow to its population and thus its power in numbers as a result of The Great Swamp Massacre during King Phillip’s War. The result being loss of land, forced removal, starvation, exposure, and threats of retribution by the English. The English declared that the Indians part in the war was an “act of rebellion” against the King of England and thus large numbers of Indians became prisoners of war, were crowded into colonial jails, faced banishment, enslavement, or execution (1). Some Narragansett people escaped (to New York and later Brotherton, Wisconsin (2). Narragansett children experienced the trauma of being taken from their parents, and many lost their lives, suffered the loss of their parents and grandparents, aunts, uncles, community, language, spirituality, culture, traditions and all ties that connected them to their heritage at the hands of the colonizers. Many of the Narragansett men, women, and children who remained were enslaved or indentured to settlers’ farms and plantations and were forced to work as farmhands and in domestic capacities. Captive Narragansett were placed in categories according to age and a sliding scale of involuntary servitude was devised. As young as 18 months (3), all Indian children under five years of age were required to do twenty-five years of service. Those aged 5 to 9 were to serve until they were 28 years, those 10-15 were to serve until 27 years, etc. (3).

Roger Williams, the Quakers and other religious groups began their campaigns to “civilize” the Indigenous peoples through their preaching, teaching and conversion to Christianity. There were also non-federal boarding schools established by the Quakers. Red Wing, one of Tomaquag Museum’s founders attended one such Quaker boarding school. Early education in Rhode Island included religious instruction along with basic academics. “There were some local efforts for the instruction of the Indians, of whom there were, in 1730, nearly a thousand (985), in the colony. These efforts began with a gift of land made by Judge Sewall, for that purpose, to Harvard College, in 1696” (4). And in 1745 the Anglican Society for the Propagation of the Gospel erected an Indian schoolhouse for the Narragansett Indigenous children on a site near School House Pond in Charlestown, RI, a wooden structure built in 1750 and used until 1880 when Rhode Island officially “detribalized” in writing the Narragansetts (5). I recall my grandmother telling me that her grandmother was one of the last students to attend school there.

Ninigret Lodge, Charlestown, Rhode Island, From What Cheer Neetop! What Cheer! Historical Picture Book. Shannock Press. Tomaquag Museum Archives

By 1839 in Rhode Island, the public school laws had been codified and the language of such as it pertains to the financial responsibility includes “white students” and “colored students” but specifically excludes the “Narragansett Indians”(6). This was the period of time in which Rhode Island was writing the Narragansett out of existence by conveniently re-identifying those Narragansett who remained as black, mulatto or otherwise. Thus any documentation which may exist must be scrutinized. I, as a Narragansett, and we, as a Tribal Nation, still exist!--no matter what the written records of the State of Rhode Island indicate.

Let me take a moment to digress. This erasure and invisibility had and still has profound affects for many generations of Narragansett people. Paulla Dove Jennings, a Narragansett-Niantic elder in 2014 while sharing experiences from her youth into adulthood writes, “We were told of our great-grandmothers and great-grandfathers. We were told of the forced sale of our tribal family lands in Charlestown. We were told of tribal gatherings, family traditions, tribal traditions, and legends with morals to guide us as we grew into adulthood. Imagine the surprise and shock we faced when we began school… “After King Philip’s War in 1675, there were no Indians in Rhode Island”, …”Indians are dirty and sly, and scalp and torture.”, “Indians are the invisible people.” She further writes “My people are the only people in the world judged by a non-Indian term called “blood quantum.” We are the only race of people who are asked: .Are you a real Indian?; Full-blooded?; Live in a tepee?, But you don’t look Indian!”(7). Dawn Dove, another Narragansett-Niantic elder wrote about the “Alienation of Indigenous Students in the Public School System” in this way. “The same history that is presented to make mainstream America feel good makes Indigenous children feel alienated and powerless.” She continues, “We don’t want “feel bad” history, but we do need inclusive, truthful history. Our textbooks have so slanted the history of the United States as to present a one-sided picture…”. She further writes, and I agree, that “Indigenous students need to feel that their history, which is a part of United States history, is valued. Students must feel valued and accepted in the larger public school system. Often our students feel isolated in that system.” (8) In fact, to quote the Tomaquag’s Executive Director and former public school teacher Loren Spears, “there is no Rhode Island history without Narragansett Indian history, and there is no U.S. history without Indigenous history.”

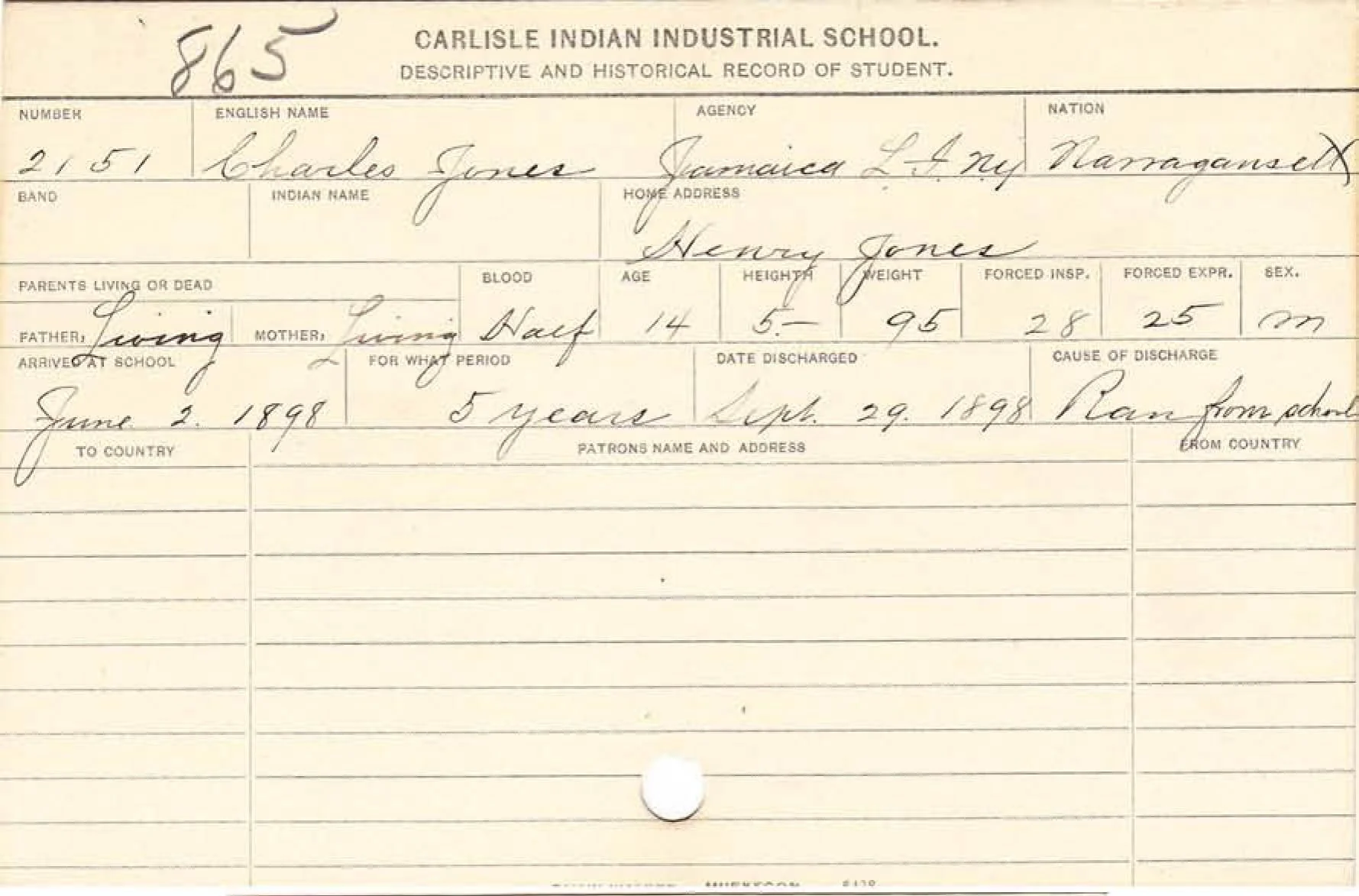

This has been the history of the Narragansett, so when the Federal boarding school system was established by Richard Pratt in the 1860s, there had already been centuries of assimilation and eradication of not just Narragansetts but other Southern, Midwestern and Eastern Tribes. There were two federal boarding schools closest to Rhode Island, namely, Hampton Institute in Virginia established in 1878-1923 for students of color and Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania established in 1879-1918. While documentation is sparse, it is recorded that a few Narragansett and Mashpee Wampanoag youth attended Carlisle Indian Industrial School (9). An example of one such Narragansett youth named Wallace Lewis who was enrolled at Carlisle Indian School from 1908 until 1911 can be found in his Descriptive and Historical Record HERE. This Descriptive and Historical Record was found through research at the Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center.

Descriptive and Historical Record of Charles Jones. Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center.

Trauma and cultural erasure continued in later years with the establishment of the foster care system when Indigenous children were taken from their own families and placed in the homes of non-Indigenous families (10). These placements continued involuntarily until the establishment of the Indian Child Welfare Act (11) and Public Law 93-638, The Indian Education and Self-Determination Act of 1974, became law. Under these statutes, tribal governments and Indian parents were given the right to determine how their children were to be educated. Also, placement of Indian children when necessary was in the homes of Indigenous family members as a primary and preferred option. As a result of these Acts, many of the boarding schools depicted in the Away From Home exhibit are still in existence but are now under the control of individual Tribes where cultural traditions, language and knowledge are taught in addition to mainstream educational curricula. As for the Narragansett Tribal children living in Rhode Island today the majority attend their local public school.

So…whether through war, murder, slavery, indentured servitude, apprenticeship, or even education; the loss of identity, culture, language, ceremony, and land has been a devastating and traumatizing experience of the Narragansett and other Indigenous citizens of this State. We as Indigenous families seek to empower our children by reminding them of their great heritage, the resilience of our ancestors and we continue to teach our fellow man that “we still remain!”

So, I leave you for now with this final thought…

In one of the books displayed at the Away From Home exhibit, Tim Giago (Lakota Sioux) in speaking about the boarding school system wrote, “It was the firm belief of the educators who came to the Indian reservations that if they could make the children over in their own image, they could more easily be assimilated into the mainstream and the “Indian problem” would cease to exist. What they failed to understand is that there never was a problem until they brought the problem. Like so many mistakes that were made in the past, the “cultural imperialism” foisted upon the Indian people was not for their own good, but for the good of those who imposed it.” (11)

Thank you for taking the time to read my blog post, this won’t be my last.! Please feel free to post your comments below. And now, I would like to share a few of your own written comments from and about the Away From Home, Stolen Relations exhibit.

“It takes all of us to recognize the trauma our ancestors have placed on our Indigenous neighbors recognize the land we stand on and make change, transformational change that our indigenous neighbors deserve.”

“I was somewhat familiar with this history. I thank it is vital that everyone who hasn’t known this part of our history learn about it so that we can understand the relationship between our past and present and create a more just legacy for our future.”

“I was not familiar with the history of this. What stood out to me the most was the kids being put in school, being forced to speak English change their appearance, and have their name changed to an English name.”

“What was most striking to me was that although many of these boarding schools were in the southwest US, the most prominent one was in Pennsylvania and many curriculums included a 1925 speech made in Boston. New Englanders sometimes forget that we can be as bigoted against race/religion/other cultures as those in the southwest are made out to be.”

“I was not familiar with the boarding school experiences that Indigenous-African students had. The quotes were the thing that affected me most and the sections about getting their hair cut off and the way students were fed…”

“What affected me most about learning this history was the appreciation many found from the schools they were forced into. Even though the schools were meant for assimilation, they found ways to hold onto their culture. That is remarkable to me.”

“I believe this history is very omitted from school courses. While I don’t believe people should be shamed for ancestors or their nationality, I think providing this history is important for a full perspective.”

“Going through the American school system, I do not believe we were properly taught about the history. It’s important to understand so history does not repeat itself more than it already has.”

“I was not familiar to the extent. White supremacy has been around for a long time. The Native Americans, Blacks, and all peoples of color have been marginalized and considered “lesser than” by whites. I am so appalled by this behavior.”

“I was not familiar with this history by any means. Two things affected me the most. First, how on earth did I have no knowledge of any of this prior to coming here. Second, I was fascinated by the way sports have always been successfully used as a means of assimilation.”

“I am 68 years old and never knew about this until a year ago. We need to teach all history in this country - not just “the good stuff”.

“Acknowledge the situations Educate about the situations Honor those affected by the situations”

“We need our government to take responsibility for what has been done to our Native Americans - still going on.”

Your responses to “Dear Student”

“Stay close to the power within you that wishes you to do and be great things”

“It may be difficult to see the reasoning why this happened to you but just remember where you came from and how strong you are, you will get through this and live to make a difference. You matter.”

“I am sorry this is happening to you”

“I wish you weren’t treated unkindly”

“Please try to remember that there is also good in the world”

“Have hope. You will return. You will not ever lose who you are.”

“You are strong, you will rewrite history and you will make huge changes. I am sorry you have had to endure such traumatic experiences. I am keeping you dear to my heart.

References Cited

(1) Rhode Island History Journal ; Vol. 37:3 August 1978 by Paul R. Campbell and Glenn W. LaFantasie “Scattered to the Winds of Heaven-Narragansett Indians 1676-1880

(2) Dawnland Voices, An Anthology of Indigenous Writing From New England, Edited by Siobhan Senier (p. 501, Thomas Commuck)

(3) Indenture of Hannah to George Mumford December 5, 1723 English Rhode Island Historical Society Providence, RI Shepley Collection Mss 9006 Vol. 15, page 19, Item ID 598, Document ID 370

(3) Rhode Island History Journal; Vol 37:3 August 1978 by Paul R. Campbell and Glenn W. LaFantasie “Scattered to the Winds of Heaven-Narragansett Indians 1676-1880

(4) A history of public education in Rhode Island, from 1636 to 1876; https://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=moa&cc=moa&view=text&rgn=main&idno=ABJ2388.0001.001pg. 10

(5) Preservation.ri.gov; historic and architectural Resource of Charlestown, Rhode Island: A Preliminary Report pg. 10 of the document

(6) A history of public education in Rhode Island, from 1636 to 1876; https://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=moa&cc=moa&view=text&rgn=main&idno=ABJ2388.0001.001pg. 51)

(7) Dawnland Voices (pg. 520-522)

8) Dawnland Voices (pg. 523-525)

9) carlisleindian.dickinson.edu/nation/narragansett); carlisleindian.dickinson.edu/nation/mashpee-wampanoag).

(10) dawnland.org

(11) ICWA title 25 U.S.C. 1902; Pub. L. 95-608, §3, Nov. 8, 1978, 92 Stat. 3069

(12) Children Left Behind, The Dark Legacy of Indian Mission Boarding Schools; p. 146; author Tim Giago