From the Archives: Cooper's Hawk

Belonging(s): “A close relationship among a group and personal or public effects”

“Asco wequassinummis, neetompooag” (Hello my friends)!

Hello! Welcome back to another installment of the From the Archives series where Collections and Archive Manager Anthony Belz shares some of the more interesting materials in the Tomaquag Museum archival collections. In this installment, we will be looking back at the earliest days of the museum, when it was located in Ashaway, Rhode Island in the Tomaquag Valley, for which the museum was named, when it was formally called the Tomaquag Valley Indian Museum.

A common theme in the From the Archives series is that of discovery. As we continue to organize and arrange the archive, there are constantly new discoveries and connections being made. These connections allow us to uncover lost knowledge and to create a fuller picture of the past, even if there are noticeable gaps in the archival record. Even small connections can lead to an increase of our collective knowledge. These connections provide historical and cultural context that allow us to not only understand the past better, but to rediscover this lost knowledge and bring it into the light.

In the photographic archive, there are a series of photographs of Everett Tall Oak Weeden with a hawk perched on his forearm, either alone or accompanied by Red Wing at his side. These black and white photographs, (one of which was turned into a postcard) are some of the best photographs of Tall Oak and Red Wing in the archive. In my opinion, the photographs are some of the best of not only Tall Oak, but Red Wing as well and are a great representation of the earliest days of the museum. These photographs, a series of 4 in various poses and angles, I thought were purely for creating the postcard (I may be right).

Everett Tall Oak Weeden. Tomaquag Valley Indian Museum, Ashaway ca. 1959-60. Tomaquag Museum Archives

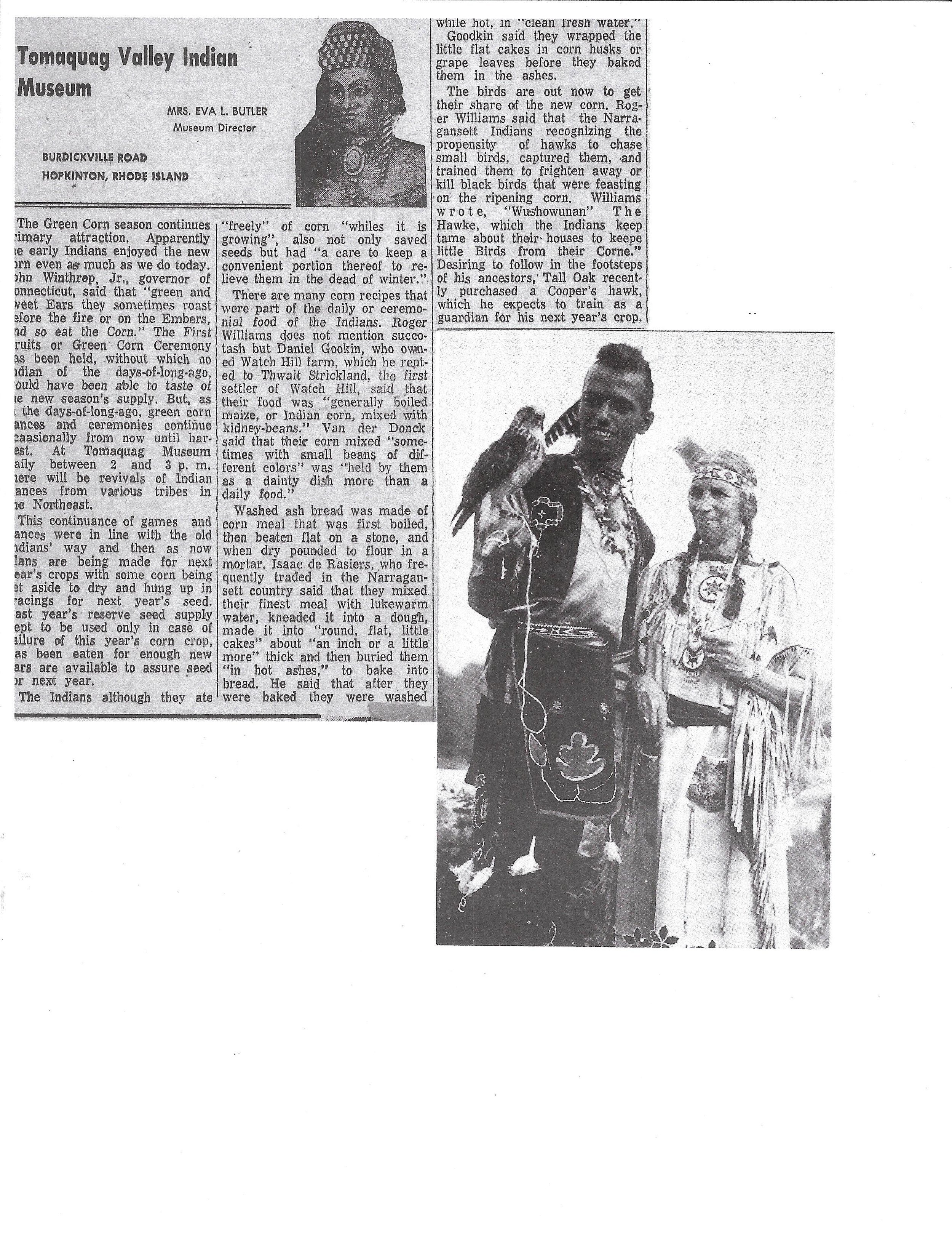

Recently, I have been organizing the archive of the museum’s first director and co-founder, Eva L. Butler as well as some of Red Wing’s archival material that was discovered by Brown University collection’s interns Allyson LaForge and Bridget Hall in the collections storage room while conducting an audit of the collections. As I was searching through Red Wing archival material found in collection’s storage, I came across a newspaper clipping of a small undated article that Eva L. Butler wrote for the Westerly Sun discussing the importance of corn, or more appropriately, maize to Indigenous people in New England. I know it was published in the Westerly Sun because I have found a few other of these articles that were on full intact newspaper pages not clipped and devoid of their publication information.

The short article, which was written by Eva L. Butler, the Director of the Tomaquag Museum and Colonial era historian, focuses on corn, or maize to the Indigenous people of New England. As she often did, she uses primary source materials from colonial records and journals, such as Roger Williams’ Key to the Language of America (Tomaquag Edition) to paint a picture of Indigenous life at the time of colonization, a time that traditional ways were drastically changing due to European incursion and influence. As I had only encountered a few of these articles written by Eva L. Bulter, it immediately piqued my interest as it related to maize, so I decided to read it. To my surprise at the very end of the article it specifically mentions Tall Oak and the hawk! It’s commonly known as a Cooper’s Hawk (Accipiter cooperi).

Corn. Article. Eva L. Butler. Westerly Sun. undated ca. 1959-60. Postcard attached. Tomaquag Museum Archives.

Excerpt from newspaper article. Eva L. Butler. Westerly Sun. undated. Tomaquag Museum Archives.

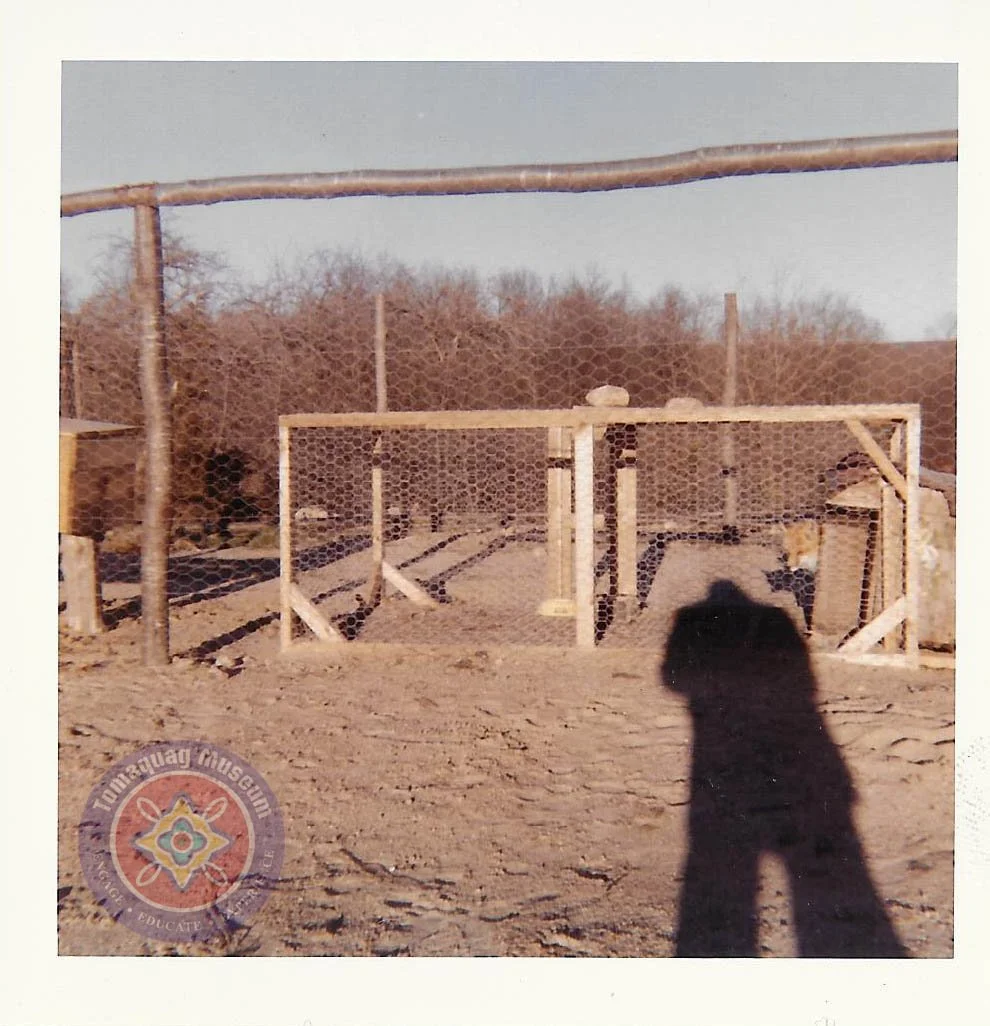

Although Key to the Language of America was published in 1643, and reprinted many times since, the connection Eva Butler made from the past to the present through Tall Oak that revitalized a cultural practice of keeping and training hawks to help protect crops. As it turns out, Tall Oak’s Cooper’s Hawk was part of a collection of live animals the Tomaquag Museum kept in Tomaquag Valley. This collection of animals included a Tom and three hen turkeys, quails, baby racoons, a deodorized skunk, Cologne, and Miskey (Mishquashim), a red fox. In the archives we have several pictures of this small zoo which documents their habitat and cages.

For Indigenous people of the world, animals have been extremely important and wholly integrated into their cultural lifeways. Animals provided people with food, clothing, tools, and in their beliefs. They symbolize many things including Mother Earth, the passage of time, and clans. By having a zoo on the premises, the early Tomaquag Museum was able to share these stories and important information with visitors of this meaningful connection.

Tomaquag Museum Zoo. Tomaquag Valley, Ashaway ca. 1959. Tomaquag Museum Archives

Tomaquag Museum Zoo. Tomaquag Valley, Ashaway. Tomaquag Museum Archives.

Juvenile Cooper’s Hawk (Accipiter cooperi) Wikimedia Commons.