From the Archives: Revitalizing Indigenous Material Culture 1927-1939

Greetings and welcome to another installment in Tomaquag Museum Belongings Blog series, From the Archives. For this blog post, longtime Tomaquag Museum collaborator and volunteer, Brown University PhD Candidate in American Studies Allyson LaForge, will share an exciting discovery she found during her archival research investigating the intertribal Indigenous organization the Sons and Daughters of the First Americans (SDFA). You can read more about another one of the SDFA’s projects, the Historical Picture Book, in this blog post by Collections Manager and Archivist Anthony Belz: From the Archives: What Cheer! "Netop" What Cheer! Historical Picture Book Plates.

The SDFA was founded in 1937 by an intertribal group of Indigenous people from southern New England, but the group emerged from a long activist tradition of resistance to settler colonialism. I began researching the SDFA for my dissertation back in 2019, when I first began volunteering in collections at the Tomaquag Museum. My dissertation research examines how Indigenous people wielded material culture as activist tools to resist settler colonialism and ensure Indigenous futurity, and I was excited to find multiple boxes of SDFA records, newspaper clippings, meeting minutes, and more in the Tomaquag Museum’s archives.

My research focuses on the SDFA’s creation, use, display, and sale of handicraft, which was a significant portion of their mission. The SDFA also engaged in multiple types of public-facing advocacy and forms of memorialization, from pageants to ceremonies like the Great Swamp Massacre Memorial Services and Pilgrimage.

The Tomaquag Museum’s archives include multiple records from the SDFA, which was officially disbanded in 1970 due to inactivity and declining membership. While the SDFA had a strong focus on material culture, with multiple members working to teach, learn, and share skills in basket-making, drum-making, and other handicraft, few images from the early years of the organization survive. When I was completing a full collections inventory of the Tomaquag Museum in preparation for its upcoming move, I found a photo journal from circa the 1930s or 40s on a shelf in the back corner of the collections storage room. This journal depicts images from the same time as the SDFA’s early years, showcasing the process of crafting a wide variety of material culture. I worked to analyze the handwritten portions of the journal alongside Archival Assistant Kate Cullen-Fry, and we both think that the images and writing in the journal are by Red Wing based on the similarity to her other handwritten and drawn documents.

While the photo journal does not include any information about who was involved in the activities depicted, it is very likely that the photos were taken at Camp Ki-Yi, which Red Wing ran between 1927 and 1939 at Applehill House, her family’s homestead and farm in Pascaog, Rhode Island. When read alongside the SDFA’s meeting minutes, which reflect its members’ dedication to crafting and teaching handicraft to future generations of Native children, the photo journal’s depiction of children learning these skills demonstrates what these processes may have looked like.

During this time period, she also helped to establish The Narragansett Dawn and the SDFA in the mid-1930s, meaning these two outlets for activism took place while she was also spending her summers teaching children. Early records indicate that participants included Narragansett and other Indigenous children as well as non-Indigenous children. Unfortunately, the photo journal is missing the first page, which may have provided answers to these questions. The final page of the journal lists sources of information that informed the journal’s research and contents, which I worked to track down to roughly date the journal. It is also possible that the journal emerged from Red Wing’s time working at Camp Wihakowi in Northfield, Vermont between 1940 and 1949, but the photographs are much more similar to Red Wing’s photographs from the 1930s.

The photographs, drawings, and written descriptions allow us to envision the kinds of work Red Wing was involved in during the years before the Tomaquag Museum was established. When read alongside the SDFA’s meeting minutes, which reflect its members’ dedication to crafting and teaching handicraft to future generations of Native children, the photo journal’s depiction of children learning these skills demonstrates what these processes may have looked like. For example, in 1938, SDFA President Christopher Noka (Narragansett) gave an “inspirational” talk to SDFA members in which he encouraged “each knowing how to do any basketry, bead work or wood work” to “teach it to the younger group of Indians and keep the children interested” (SDFA Meeting Minutes, April 1, 1938). The crafts that Red Wing taught children to do at Camp Ki-Yi and other settings reflected her skills in teaching children about crafting practices.

Camp Ki-Yi Brochure. Red Wing Papers. Tomaquag Museum Archives.

This journal may also have been an early collaboration between Eva Butler and Red Wing, based on the citation of Butler’s “Eastern Algonquin Indians” text in the credits. Butler also published a 1930 children’s book, “Along the Shore,” which was one of her only publications. However, this book was not about Indigenous material culture, but rather about marine creatures.

On the second page of the photo journal, which is the first page that we still have access to, we can see a group of children firing clay products made from gathering “Materials Found Around the Brook.” Each page of the photo journal focuses on a specific environment, reflecting the interrelationship between land-based knowledge and material culture practices. Red Wing illustrated two types of clay pots and a clay pipe. The page lists “clay - many colors, white, red, blue-green, pink, yellow, gray” for the creation of bowls, charms, animals, and pipes.

Camp Ki-Yi Photo Journal. Page 2. Red Wing Papers. Tomaquag Museum Archives.

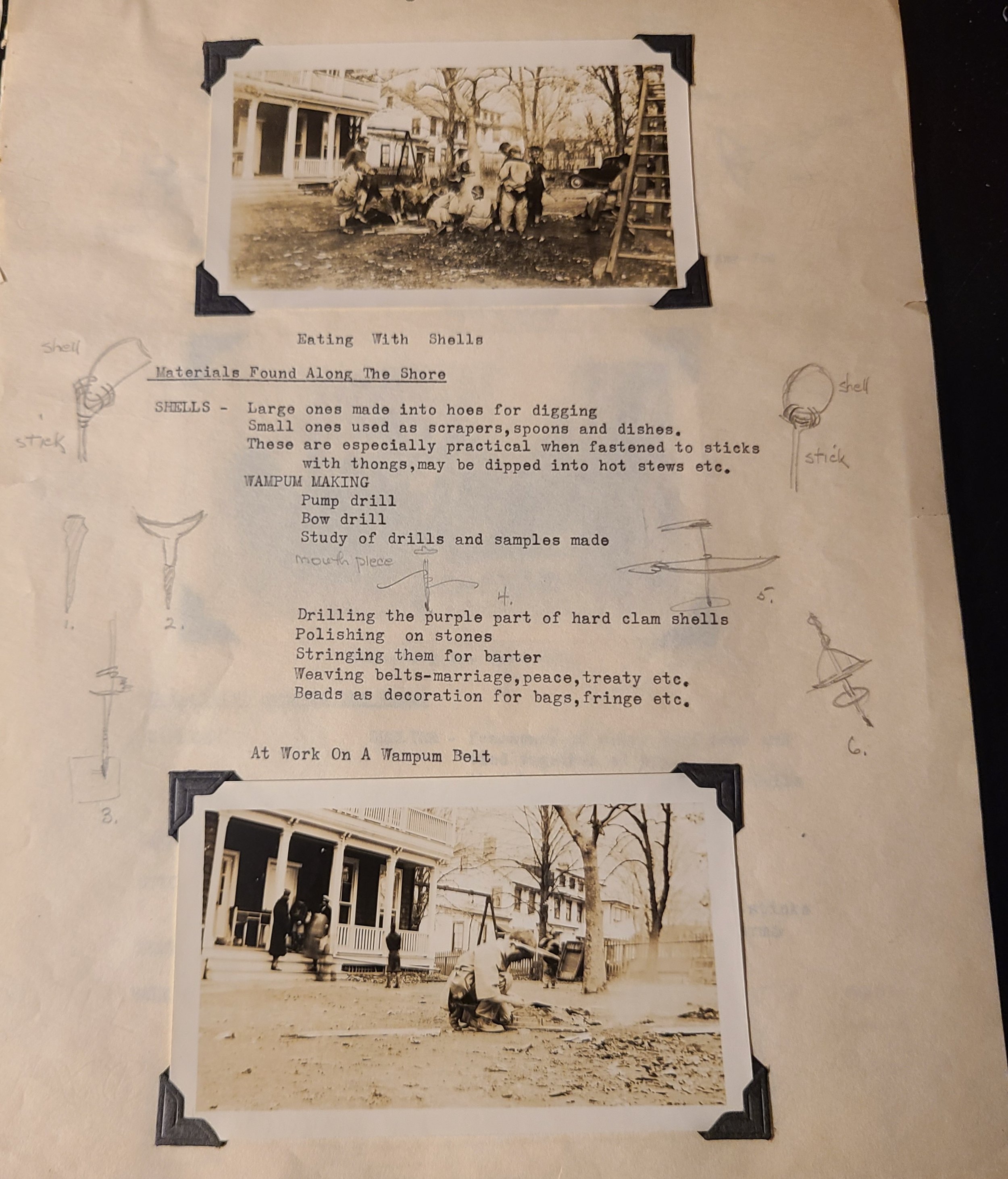

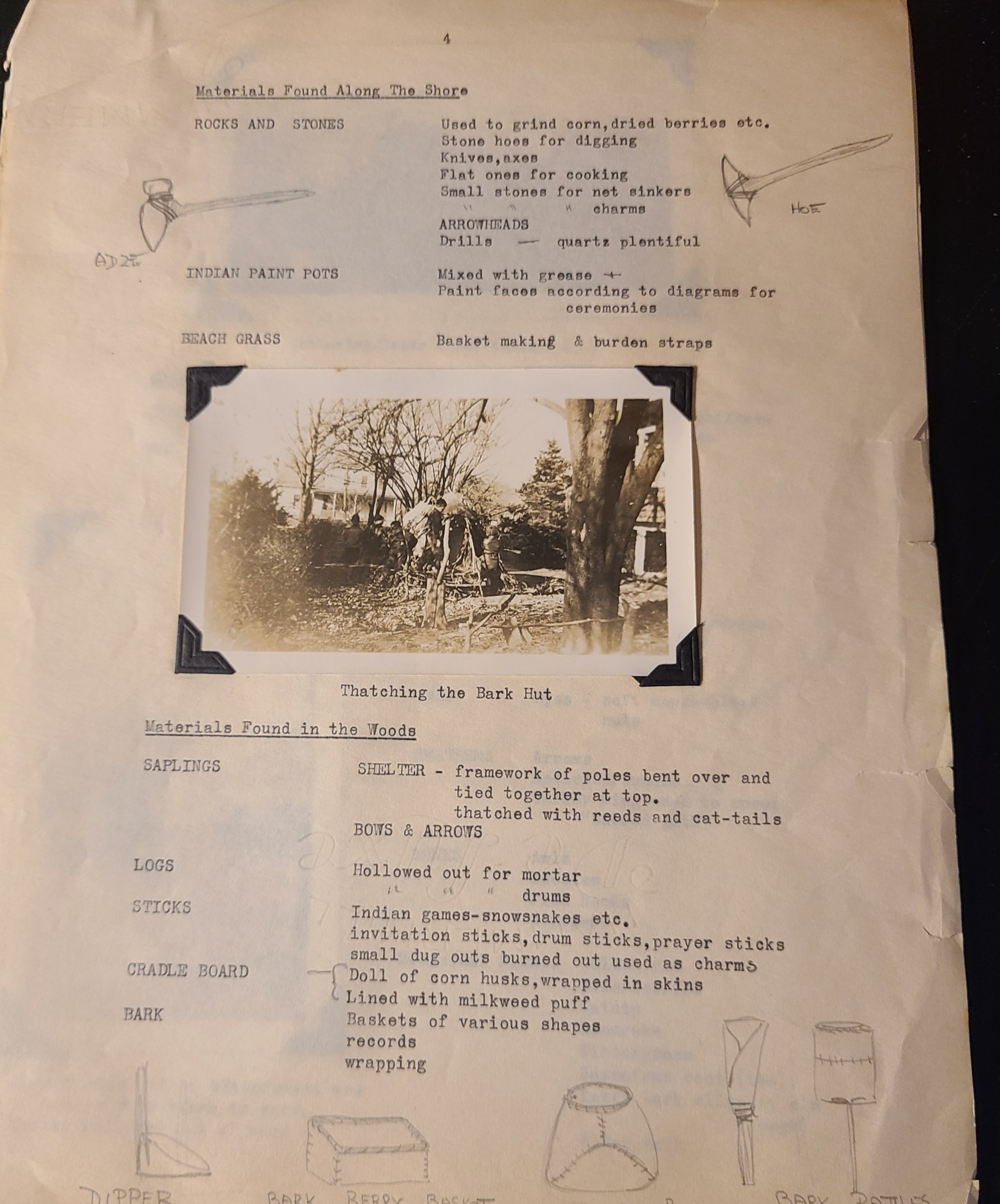

The third and fourth pages show two activities related to “Materials Found Along the Shore,” including “Eating With Shells” and “At Work on a Wampum Belt.” Around the images and text, Red Wing illustrated the process of making a pump drill. On the following page, the section on the shore activities continues with illustrations of a hafted hoe and adze.

Camp Ki-Yi Photo Journal. Page 3. Red Wing Papers. Tomaquag Museum Archives.

Camp Ki-Yi Photo Journal. Page 4. Red Wing Papers. Tomaquag Museum Archives.

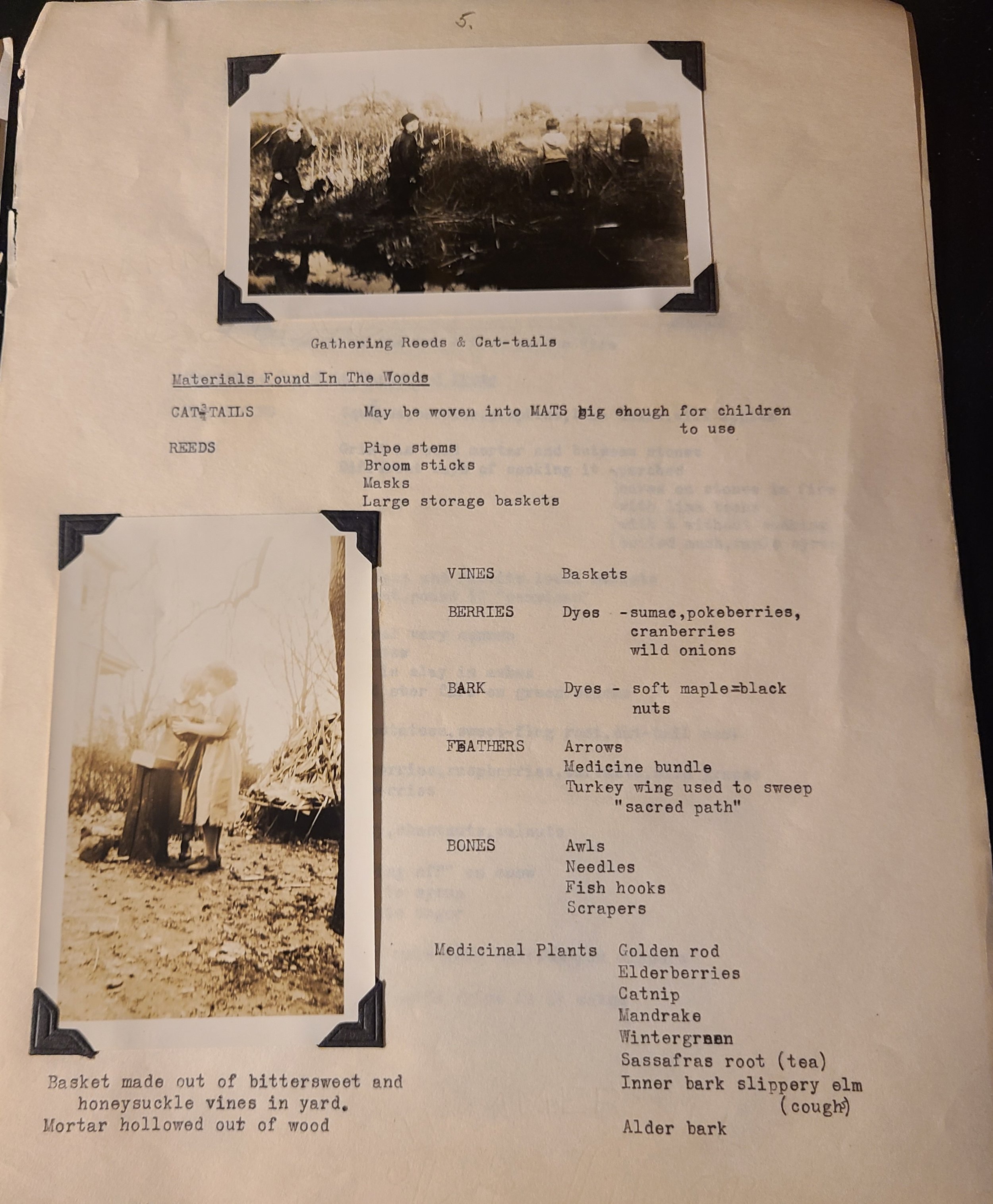

The fourth and fifth pages also show “Materials Found in the Woods,” with a photograph of children “Thatching the Bark Hut.” On the bottom of the page, Red Wing illustrated multiple types of belongings created with materials from the woods like bark, roots, and sticks: a dipper, bark berry basket, covered box, and bark rattles. On the fifth page, the children are “Gathering Reeds & Cat-tails” to weave into hats. Another image shows a “Basket made out of bittersweet and honeysuckle vines in yard” and “mortar hollowed out of wood.” The page also lists various types and uses of vines, berries, bark, feathers, bones, and medicinal plants.

Camp Ki-Yi Photo Journal. Page 5. Red Wing Papers. Tomaquag Museum Archives.

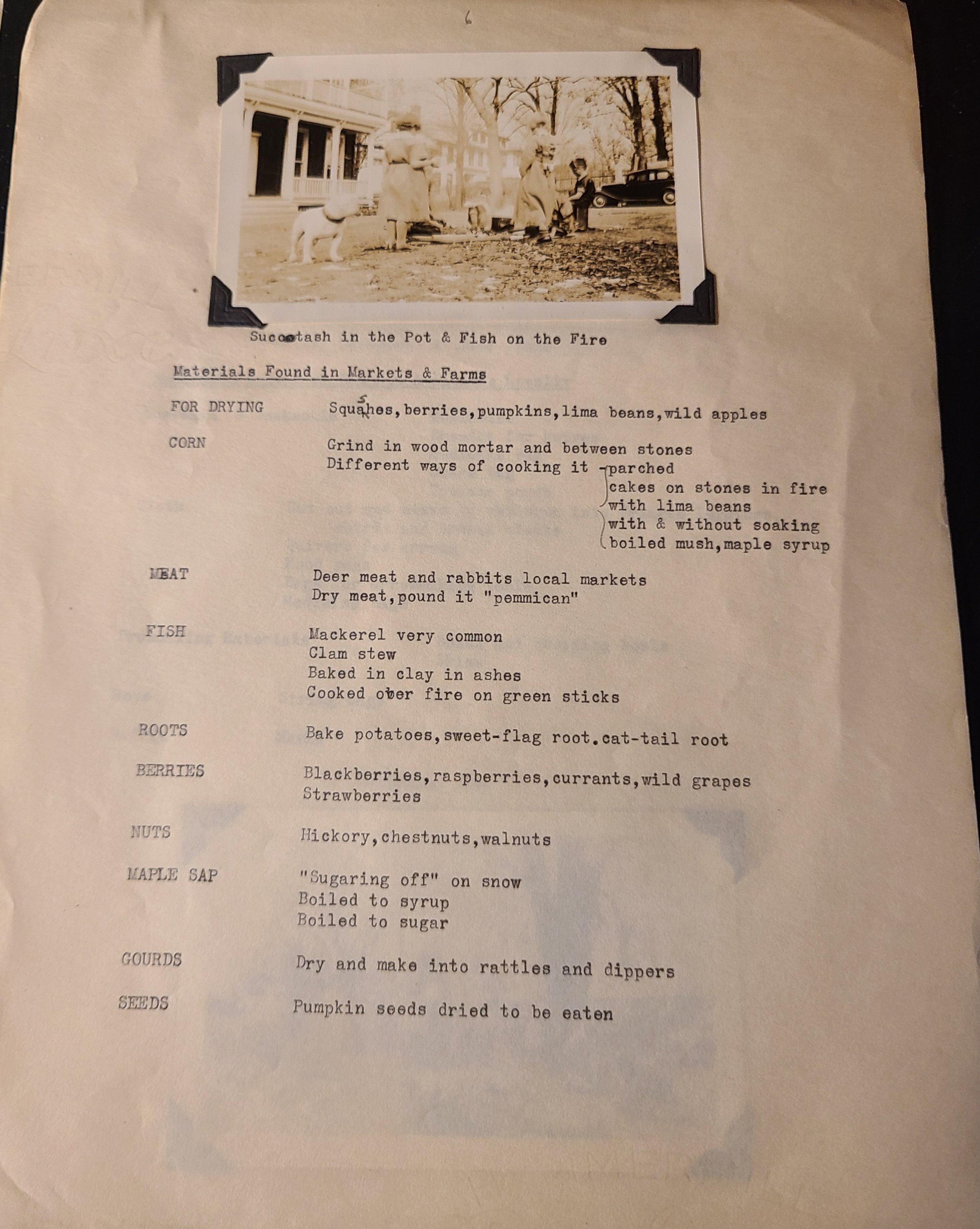

On the sixth page, “Materials Found in Markets & Farms,” the first photograph depicts children, two adults, and a dog standing around “Succotash in the Pot & Fish on the Fire.” The page lists multiple local Indigenous foodways that were still available for purchase at markets and farms, including their traditional preparations, such as drying deer and rabbit meat and pounding it to make “pemmican.”

Camp Ki-Yi Photo Journal. Page 6. Red Wing Papers. Tomaquag Museum Archives.

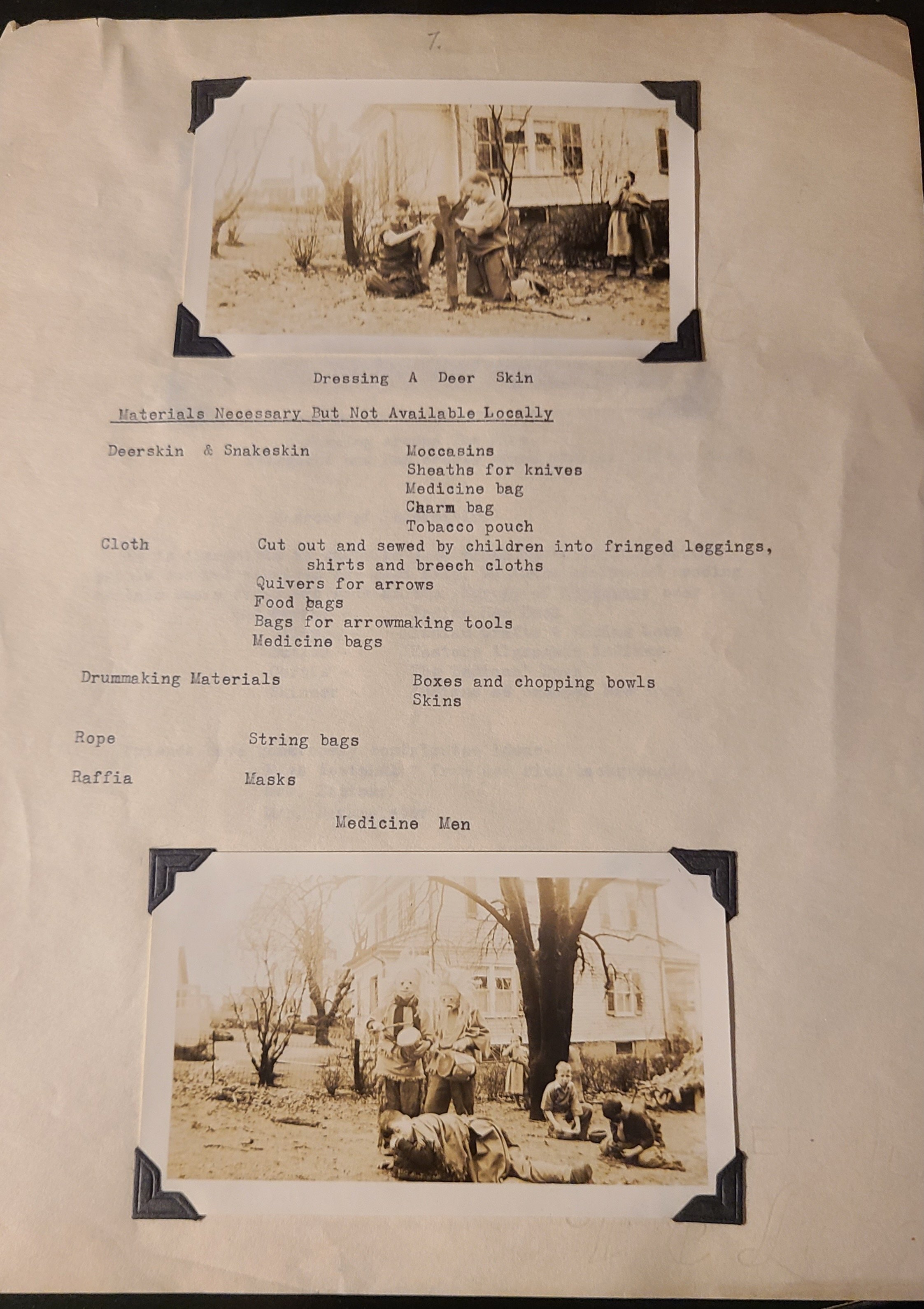

The seventh page of the photo journal also includes the final section of materials: “Materials Necessary but Not Available Locally.” This includes deerskin and snakeskin, which would have been available through hunting, but likely was not acquired locally for this specific project. The photograph shows the process of “Dressing a Deer Skin,” which likely used a skin from elsewhere, as did the creation of drums. The participants also used cloth to make clothing, quivers, and bags. Other materials included boxes and chopping bowls, rope, and raffia. The final image, of “Medicine Men,” showed the clothing and drums in use. While some of these activities would not be appropriate for outsiders to practice today, the photo journal is not specific about who participated. The SDFA documented several instances of their decision not to prioritize white children in their activities and to instead focus on Native children. However, the identity of the children and participants in this photo journal is unknown. If anyone has any ideas, please feel free to comment below!

Camp Ki-Yi Photo Journal. Page 7. Red Wing Papers. Tomaquag Museum Archives.

These activities remind me of the amazing work the Tomaquag Museum is doing in the present-day to educate about traditional ecological knowledge, like the amazing guided Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) hikes around the Tomaquag grounds led by educators. Like the children in these photographs, visitors to the Tomaquag Museum can also play traditional games and learn traditional arts. It’s astounding to think about the long history of these types of educational activities and how incredible it is that the Tomaquag Museum maintains these programs today and into the future.

From the Archives Series supported by the National Historical Publications & Records Commission.